Are Energy Performance Certificates accurate?

Contents |

[edit] Background and criticism of EPC's

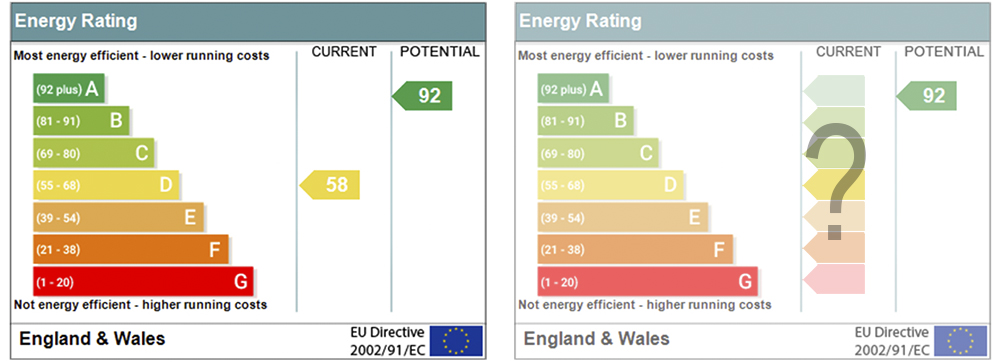

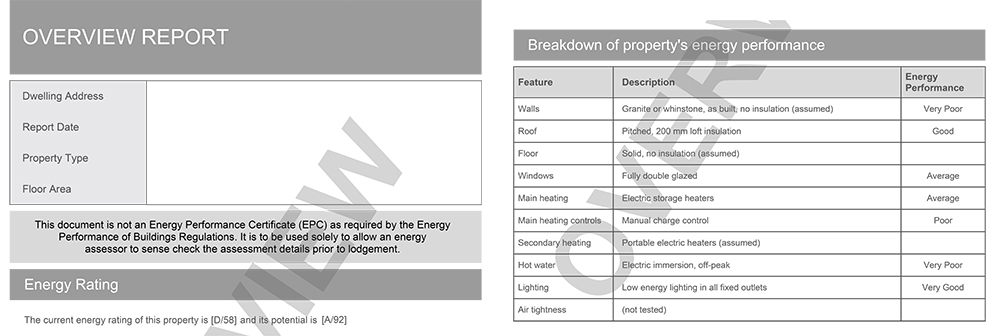

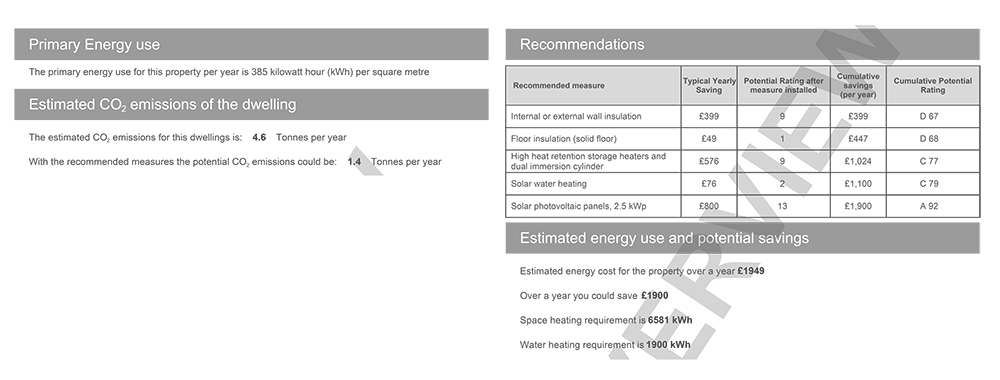

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) are required when buildings are built, sold or rented. Via a brief assessment they allocate a building energy efficiency rating from the most efficient (A) to the least efficient (G). The certificate also highlights energy efficiency improvements that could be made to improve the rating, with indicative costs verses benefits.

The concept of the energy performance certificate (EPC) stemmed from a European Union Directive entitled the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) which was introduced to the UK in 2003. The intention was to find some way of rating buildings on the same basis to create indicative bar ratings, in the same way as energy labels.

Energy labels had been introduced in the 1990's to increase awareness of how efficient individual appliances were. The programme was considered successful in that it drove innovation and slowly changed the market of for example white goods resulting in only better performing products being available. Product improvements were significant enough that in 2011 new gradings of efficiency had to be introduced in A+, A++ and A+++. Today very few products at the lower ends of the scale are sold.

[edit] Criticism of EPCs

Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) have for quite some time been criticised, for their ability to be overarching and accurate. In 2019 a study of the 'Impacts of inaccurate area measurement on EPC rating" suggested up to 2.5 million EPCs were inaccurate because of floor area assumptions. In 2021 the Government itself published "Improving Energy Performance Certificates: action plan - progress report" reporting on progress against the 35 actions outlined in their EPC action plan, published in September 2020. These were based on a call for evidence on Energy Performance Certificates (‘EPCs’) launched in July 2018.

Whilst the Simplified Building Energy Model (SBEM) which forms the basis of EPCs in the non-domestic sector was updated in June 2022 (version 6.1b), as too was the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP version 10.2) for dwellings, the current version of the Reduced Data Standard Assessment Procedure (RdSAP v9.94) which is often used for existing buildings is expected for release only in 2024.

The Sunday Times reported in February 2023 what it called 'staggering inaccuracies' with the certification scheme, referencing research by CarbonLaces, which indicated overestimation in energy use by up to 344%. At the time whilst many agreed EPCs are not perfect, some highlighted that too much was being expected of the tool, in terms of their original purpose. Andrews Sissons of social innovation agency Nesta pointed out “EPCs are not meant to measure actual energy use, but how efficiently a home uses energy. These aren’t the same thing. Many inefficient homes, for example, are under-heated because their occupants can’t afford enough energy".

More recently in March of 2023 paper “The over-prediction of energy use by EPCs in Great Britain: A comparison of EPC-modelled and metered primary energy use intensity” was published. This showed that whilst EPCs in bands A-B were relatively accurate, the picture lower down the scale was somewhat different, with bands F-G over estimating energy consumption by up to 50%. Importantly in this work the researchers said “Unlike previous research, we show that the difference persists in homes matching the EPC model assumptions, regarding occupancy, thermostat set-point and whole-home heating; suggesting that occupant behaviour is unlikely to fully explain the discrepancy.”

[edit] The nature of EPC's and building assessments

There is some indication that one of the possible reasons for discrepancy in EPC results may be the use default U-values, which are more likely to be used in older buildings, where values are unknown, than in newer buildings with build evidence and documentation. The paper “Determining realistic U-values to substitute default U-values in EPC database to make more representative; a case-study in Ireland” concluded that “Inherent in all EPC methodologies are trade-offs between reproducibility, accuracy, assessor expertise and costs. During an assessment, where accurate building data acquisition would be excessively invasive or costly, nationally specified default values are used. Default values are necessarily pessimistic to; avoid a better-than-merited rating, enable homeowners to know the advantage of energetic refurbishment, encourage homeowners to record upgrades informing EPCs, and propel assessors to seek-out information to provide an accurate rating.” However, in reviewing default U-value use across Europe and the UK before focusing on Ireland, it found "1 in 3 entries… characterised on default U-values in 2020, leading to the dataset presenting an overly pessimistic view of the stock, thus lacking validity.”

It is therefore important to note that EPC's are, and always were, intended as indicative, they were introduced as a way to make a broad sweeping assessment of building stock, which unlike the energy labels for individual appliances, have a greater number of variables that relate to performance. For example, occupancy; whilst all buildings differ in occupancy patterns, EPCs are generally based on the same average occupancies, as opposed to being tailored to individual households. The general form of buildings, sizes of windows, walls, roof etc and their indicative performance is however assessed on an individual building level. The energy used is calculated in the tool as opposed to being based on actual energy used in a building, in some cases with reference to default values.

An EPC includes a certificate of performance showing where the building performance lies on a scale of A-G, and shows where an EPC could be if improvement measures are made. An accompanying report, outlines where the building performance could be improved, giving indicative cost savings and the number of points a certain action would gain. These recommendations can help occupiers make certain choices, however in some cases these recommendations should also be further investigated. Actioning the recommendations regarding insulation levels, may also impact the potential for government support to improve energy performance, for example the Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS) requires that where insulation improvements appear on an EPC report, these must be carried out prior to seeking funding support for the installation of any boiler replacement such as heat pumps for example.

Other building assessment methods exist for non-residential buildings that are based on actual energy used, these are referred to as Display Energy Certificates (DECs). Since January 2013 DEC's have been required in buildings over 500m2 that are occupied by public authorities or institutions providing a public service, they also need to be displayed near the entrance of the building. Other optional assessment methods that look in more detail at the performance of buildings are referred to as Post Occupancy Evaluations (POEs) or Building Performance Evaluations (BPEs).

[edit] EPCs for non-domestic buildings

The basis of the EPC for non domestic buildings uses a mathematical model called the Simplified Building Energy Model (SBEM), which is a Government approved methodology and is a requirement for any new build, refurbished or extended commercial building larger than 50m2. The SBEM calculations consider building fabric, heating, hot water, cooling, ventilation and lighting and produce a Building Regulations UK Part L (BRUKL) report as evidence that a building complies with the Building Regulation requirements.

Other modelling tools are also available and often used, they can normally also produce a BRUKL report as one output, the SBEM and approved tools can usually also take into consideration any renewable technology employed on the building. The report looks at the overall energy performance and carbon emissions in terms of a Target Emission Rate (TER), which is an 'as designed' model that meets the regulations, and in terms of Building Emission Rate (BER), the assumed figure for the building in question or as built rate. If the BER given in the report is lower than the TER then the building is said to comply with the Building regulations Part L2, if it is higher then it does not comply and needs to be improved until it does. The EPC can then be produced based on the Building Emission Rate.

For larger public buildings a Display Energy Certificate (DEC) is required. This is a different methodology from an SBEM and EPC because gives an indication of the energy performance of a building based on actual energy consumption, as opposed to modelled energy consumptions, comparing it to a modelled building of a similar use and type.

The SBEM tool has been updated and improved at regular intervals since it was launched, the most current version being SBEM non-domestic version 6.1b which was updated in June 2022. These changes to the modelling tool incorporated allowances to support the changes in the building regulations as well as adjustments to the carbon factors of different energy sources. That means the average accepted carbon emissions that are associated with using a particular fuel. For electricity, because of the increased contribution of renewable energy sources contributing to the grid the associated emissions per KWh has reduced, whilst at the same time has remained the same or increased in terms of associated emissions.

[edit] EPC's for domestic buildings

There are in fact two versions of the same modelling tool that are used to calculate the energy performance of domestic buildings and in turn produce domestic EPC's.

In the same way that SBEM has been updated at regular intervals since its launch, so to has the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) for dwellings. The current SAP is version 10.2 which was introduced in 2022 and is for use on new dwellings. The elements that were adjusted included; shower flow rates, lighting efficacies, heating networks, chimneys and flues, MVHR, flow temperature for heat pumps and condensing boilers, hybrid systems, PVs, battery storage and diverters, solar thermal for space heating, heating patterns, controllers and building characteristics as well as prices, similarly to SBEM the emissions and primary energy factors.

The second version of SAP which is often used for existing buildings and refurbishments is called the Reduced Data Standard Assessment Procedure (RdSAP) the current version of RdSAP v9.94 was launched in 2012 but an updated version of the model is expected to be released in 2024, most likely with similar updates as were made to in SAP10.2.

The Government document "Energy Company Obligation SAP and RdSAP Amendments" was published in September 2023.

[edit] Why might some EPCs be inaccurate?

There are various reasons as to why EPCs might be inaccurate

[edit] Assumptions and estimates

EPCs are often generated based on a number of assumptions and estimates, because the EPC survey is not a detailed analysis. For example if wall U values are not known, then for historical buildings default U values may be used, these values may be taken for buildings built prior to a certain era, for example the 1970's or pre 1900. In some cases the actual U-values of a building, even a historical building may be better than those being assumed in the defaults. This could apply to any building, but walls, floors and window performance might be particularly difficult. Other variables that could be assumed might be the efficiency of appliances or services and the way the building is used in terms of occupancy.

[edit] Modelling software

EPCs are generated using energy modelling software, which is by its nature simplified. If the data modelling software or the data input into the software is flawed or if data from within the model is outdated, it can result in inaccurate predictions of a building's energy efficiency. If older versions of SBEM or SAP are used and outdated fuel carbon factors are used this could lead to higher or lower emissions or if the current software itself is outdated. For example the current version of RdSAP is version 9.94 and was launched over 10 years ago in 2012.

[edit] Inaccurate data points

It is still possible to make mistakes on the measured data points even if default values are not used. For example the thickness of insulation in a loft or walls, the impact of cold bridges or missing certain features that may improve or decrease energy performance. Other key data sets derived from measurements may also be simply miscalculated or inaccurate, for example envelope area, sizes of windows or floor areas. Even the slightest increase or decrease in floor area can have a relatively significant impact on the energy use rating because it is normally calculated on KWh per meter square of floor area.

[edit] Changes over time

EPCs are valid for 10 years and so in this time, various aspects of a buildings can change significantly for the better or the worse. Renovations, retrofits, or changes in occupancy patterns can all impact the reality of energy efficiency.

[edit] Occupant behaviour

EPCs tend to assume a set occupancy rate as well as patterns of behaviour, such as the set-points for heating and cooling, as well as the use of lighting and appliances. The reality of energy use in a building can vary dramatically in terms of how it is used, what equipment is installed and how it is used, ie peoples behaviour.

[edit] Climate and weather

The EPC methodology has to make certain assumptions about the weather. Average weather patterns for a certain period may differ to actual weather patterns. Weather conditions can significantly impact a building's energy performance and can impact different types of buildings in different ways, for example, how light weight or heavy weight buildings behave in cold winters or particularly hot summers and how occupants react to this. For example running fans to cool spaces down.

[edit] Human error

EPCs are produced relatively quickly after short site visits, and although assessors need to have formal qualifications there is always the possibility for human error in the calculations or data input.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Accredited energy assessor.

- Air tightness.

- BS EN 15232 Energy performance of buildings: impact of building automation, controls and building management.

- Building performance.

- Building Performance Evaluation.

- Building performance metrics.

- Building Regulations UK Part L (BRUKL)

- Carbon ratings for buildings.

- Certificates in the construction industry.

- Display energy certificate.

- Emission rates.

- Energy certificates for buildings.

- Energy efficiency of traditional buildings.

- Energy Performance of Buildings Directive.

- Energy related products regulations.

- Energy Savings Opportunity Scheme.

- Energy targets.

- Green mortgage.

- Home information pack HIP.

- Homebuyer Report.

- How much does it cost to sell my home.

- Listed buildings.

- Minimum energy efficiency standard (MEES).

- Minimum energy efficiency standard regulations for domestic and non-domestic buildings.

- NABERS UK.

- National Calculation Method.

- National Retrofit Strategy NRS.

- Non-domestic private rented property minimum standard.

- Passivhaus vs SAP.

- Performance gap.

- Post Occupancy Evaluations.

- Private rented sector regulations and traditional buildings.

- Retrofit.

- Simplified Building Energy Model.

Featured articles and news

Infrastructure that connect the physical and digital domains.

Harnessing robotics and AI in challenging environments

The key to nuclear decommissioning and fusion engineering.

BSRIA announces Lisa Ashworth as new CEO

Tasked with furthering BSRIA’s impressive growth ambitions.

Public buildings get half a million energy efficiency boost

£557 million to switch to cleaner heating and save on energy.

CIOB launches pre-election manifesto

Outlining potential future policies for the next government.

Grenfell Tower Inquiry announcement

Phase 2 hearings come to a close and the final report due in September.

Progress from Parts L, F and O: A whitepaper, one year on.

A replicated study to understand the opinion of practitioners.

ECA announces new president 2024

Electrical engineer and business leader Stuart Smith.

A distinct type of countryside that should be celebrated.

Should Part O be extended to existing buildings?

EAC brands heatwave adaptation a missed opportunity.

Definition of Statutory in workplace and facilities management

Established by IWFM, BESA, CIBSE and BSRIA.

Tackling the transition from traditional heating systems

59% lack the necessary information and confidence to switch.

The general election and the construction industry

As PM, Rishi Sunak announces July 4 date for an election.

Eco apprenticeships continue help grow green workforce

A year after being recognised at the King's coronation.

Permitted development rights for agricultural buildings

The changes coming into effect as of May 21, 2024.