Greywater recycling at the Millennium Dome

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Thames Water, struggling to balance increasing demand in the densely-populated south-east, an area which receives less annual rainfall than some Mediterranean regions, approached the New Millennium Experience Company (NMEC) suggesting a collaborative effort to develop an innovative approach to water management on the site of the Millennium Dome in Greenwich. The main objectives of the project included demonstrating and researching water recycling technologies, evaluating water efficient appliances and investigating public attitudes to water recycling initiatives.

[edit] The Parameters

The New Millennium Experience Company anticipated a maximum attendance of 35,000 people per day, and over ten million during the course of the exhibition year. This yielded a requirement for 500m3 per day for wc and urinal flushing. Three potential sources of secondary water for recycling were identified on site:

[edit] Rainwater

The surface area of the Dome itself is some 90,000m2. Rainwater run-off from the roof is collected via a gutter and channelled through specially designed hoppers, which feed into the surface water drainage system. A maximum of lOOm2/day can be collected in this way.

[edit] Greywater

Greywater was collected from the handbasins and staff showers m the Dome's six core buildings. The expected visitor numbers were predicted to use on average 120m2/day of handbasin water.

[edit] Groundwater

London has had a problem with rising groundwater since 1970 due to a decline in pumping rates, caused by the changing industrial and commercial base. A 11Orn borehole was drilled on the site and water pumped direct from the aquifers.

[edit] Treatment Methodology

A range of treatment options were available. The Dome provided the opportunity to implement a re-use scheme at full scale and demonstrate the full range of innovative treatment options.

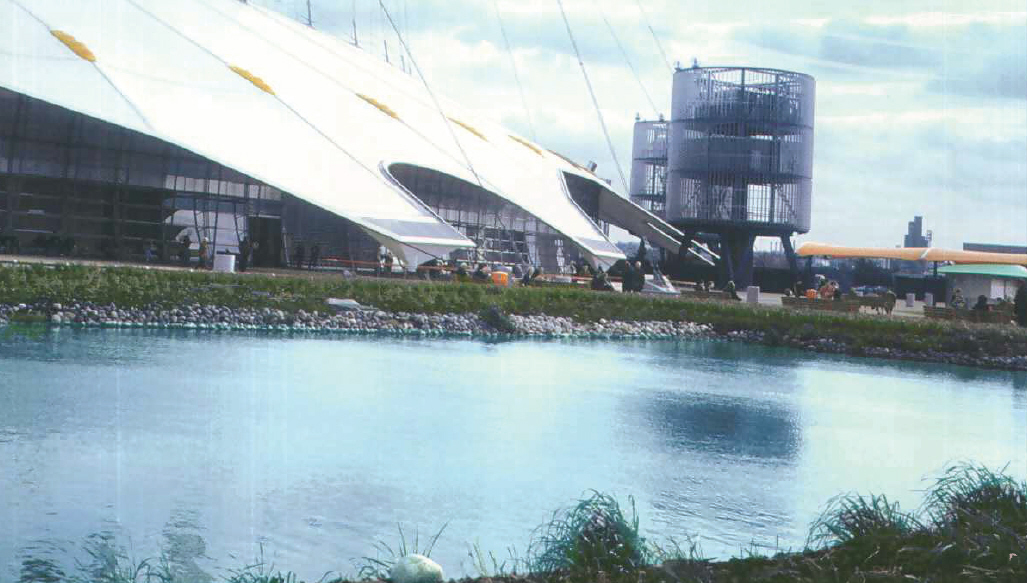

Since the rainwater run-off was collected swiftly and thus uncontaminated, open reedbeds were an appropriate choice. Rainwater was passed through the first reedbed, designed for stormwater treatment, followed by a second reedbed that functioned as a storage lagoon. The latter also performed a tertiary treatment function. The beds, approximately 0.6m deep, had a 0.5% gradient, and were filled with washed river gravel planted with the common reed. An arrangement of educational boards and a walkway running through this landscape allowed the general public to understand the operation of this 'natural' form of water treatment.

The primary concern in treating greywater is to meet the quality criteria for pathogen kill. Another key concern is ensuring minimal potential for biological regrowth in the reclaimed water.

Thames Water Research carried out a range of pilot scale trials using biological aerated filters (BAF) followed by a variety of membranes with specific emphasis on soluble bio-chemical oxygen demand (BOD) removal using synthetic greywater. Another consideration was dealing with modern soaps that would be contained in the greywater discharge. The trials indicated that tight ultra-filtration membranes were the most appropriate for handbasin and shower greywater.

Water from the borehole was tested to establish the groundwater quality. A problem with hydrogen sulphide gas was experienced together with a much higher than anticipated salt and iron content. A system was devised to dose the groundwater with hydrogen peroxide to oxidise any metal contaminates, then pass the water through granular activated carbon to remove the organic contaminates. Membrane filtration followed carbon exchange where ultra-filtration removed residual organics and a reverse osmosis (RO) membrane desalinated the groundwater. As RO filtration was needed to remove the salt from the borehole water, it was therefore combined with the BAF treated greywater and rainwater from the reedbeds through the same membrane configuration. The treated water was then re-hardened and disinfected before being pumped back into the Dome for flushing the WC's and urinals.

[edit] Distribution networks

The distribution elements of the recycling systems became a significant part of the water services systems for the Dome. A dual-system of drainage was required - conventional 'foul' water from toilets and kitchen disposals, and 'greywater' from showers and wash handbasins , as well as a dual system of water supply pipework - conventional potable water and 'reclaimed' water to serve the WC's. A protocol needed to be developed for the reclaimed water pipework: purple coloured pipe used in the United States was already in use for another service, so black pipe with four longitudinal green stripes was adopted. In total , 692 WC's and 220 urinals were served with reclaimed water, with 277 wash handbasins providing greywater.

[edit] A recycling demonstration showcase

The recycling plant at the Millennium Dome was the hub of Thames Water's research into water use and conservation. It was staffed by full-time Thames Water research scientists as well as students with on-going research collaboration . During the lifetime of the 'Millennium Experience', the plant was fully evaluated under operational conditions. One of the key areas was to establish the appropriateness of this type of recycling scheme, both in terms of reliability and cost effectiveness. In addition, a variety of water-saving devices were used in the public toilet blocks in the core buildings, allowing comparative research into water usage, and educational material displayed to ascertain the influence if any - of education on visitor behaviour.

The fast-track and constantly evolving nature of the project required a collaborative team approach, with the New Millennium Experience Company, Thames Water, various consultants, contractors and suppliers combining expertise to ensure completion of this unique facility on time.

The implementation of a recycling scheme at the Millennium Dome site with the potential to use the venue for on-going public education and academic research in water efficiency and conservation was a major opportunity for the UK water industry and anyone with an interest in sustainable water management into the 21st century.

This article first appeared in Patterns, written by Chew Pieng Ryan and published in 2001. It is reproduced here with kind permission of --Buro Happold.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

Infrastructure that connect the physical and digital domains.

Harnessing robotics and AI in challenging environments

The key to nuclear decommissioning and fusion engineering.

BSRIA announces Lisa Ashworth as new CEO

Tasked with furthering BSRIA’s impressive growth ambitions.

Public buildings get half a million energy efficiency boost

£557 million to switch to cleaner heating and save on energy.

CIOB launches pre-election manifesto

Outlining potential future policies for the next government.

Grenfell Tower Inquiry announcement

Phase 2 hearings come to a close and the final report due in September.

Progress from Parts L, F and O: A whitepaper, one year on.

A replicated study to understand the opinion of practitioners.

ECA announces new president 2024

Electrical engineer and business leader Stuart Smith.

A distinct type of countryside that should be celebrated.

Should Part O be extended to existing buildings?

EAC brands heatwave adaptation a missed opportunity.

Definition of Statutory in workplace and facilities management

Established by IWFM, BESA, CIBSE and BSRIA.

Tackling the transition from traditional heating systems

59% lack the necessary information and confidence to switch.

The general election and the construction industry

As PM, Rishi Sunak announces July 4 date for an election.

Eco apprenticeships continue help grow green workforce

A year after being recognised at the King's coronation.

Permitted development rights for agricultural buildings

The changes coming into effect as of May 21, 2024.